The Murders That Ended The Hawkhurst Gang

Two killings that shocked 18th-century Britian

In 1740s Britain, a pair of murders in Sussex would captivate the public imagination. Acts so brutal, they would destroy Britain’s most dangerous smuggling gang and drive a government purge of the Sussex smuggling community: the murders of customs officer William Galley and shoemaker, Daniel Chater.

In October, 1747 the Hawkhurst Gang, Britain’s most feared smugglers, broke open the customs house in Poole, Dorset, emptying it of its tons of tea. The tea originally belonged to a gang of Chichester smugglers, who had lost it to a customs seizure the month before. They didn’t have the guns or chutzpah to rob a customs house, so they hired a smuggling gang that did: the paramilitary Hawkhurst Gang.

The raid was a spectacular, if unsubtle, success. Both gangs rode into town the next morning to adoring crowds, which included a young shoemaker, Daniel Chater. Chater knew one of the Chichester smugglers, who greeted him and handed him a small bag of tea from the raid. He wasn’t involved in either gang, but his familiarity was enough to alert the authorities investigating the raid. Customs officer William Galley took Chater to see the Surveyor General for Sussex for questioning, carrying a letter explaining their purpose.

The pair got turned around on their way, and stopped for a drink at the White Hart pub, which, unknown to them, was the Chichester smugglers’ hangout. The pub landlady suspected them to be informants, secretly putting out the call to the gang. They couldn’t see the smugglers trickling into the pub, as the landlady plied the informant and lawman with drinks. The alcohol eventually got to Galley and Chater, who passed out in the back of the pub. While they were sleeping it off, the letter in Galley’s pocket confirmed the smugglers’ suspicions.

The gang wasn’t actually sure what to do with them. They couldn’t just let them go, Chater’s information could send some of the gang to the gallows. They considered holding the pair hostage or selling them to the French prison galleys, but that seemed too good for a snitch and his handler. No, the smugglers would make an example of them.

They beat the customs man and his informant, then dragged the drunk bruised men out to their fate, leaving nothing but a threat to shoot anyone in the pub who reported what they saw. The gang murdered them slowly over the course of several days, a cruelty born out of hesitation as much as viciousness. Galley and Chater’s improvised, public kidnapping had meant that there were plenty of witnesses. The smugglers wanted to make sure they were all responsible for the killing; the blood on their collective hands would prevent them from betraying each other.

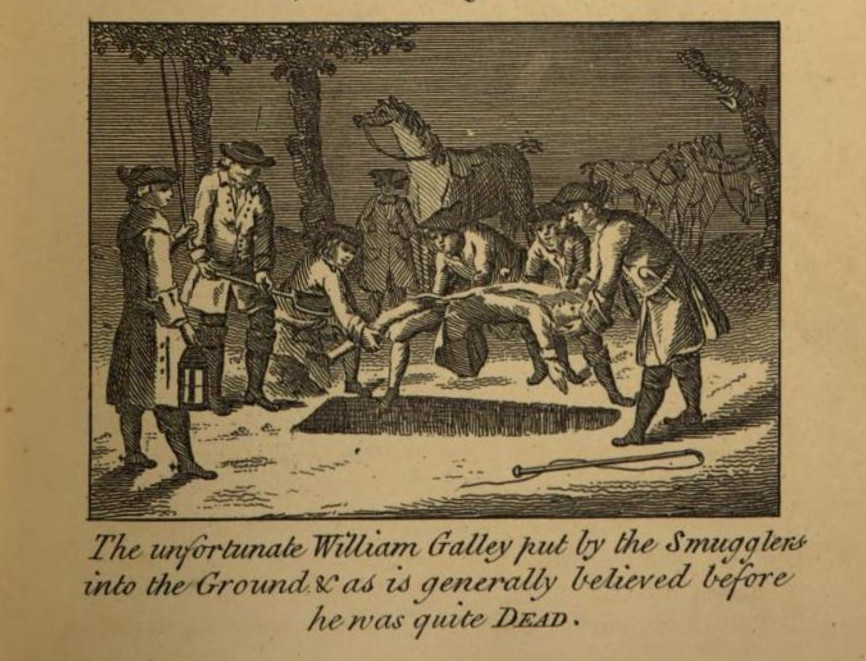

Galley was beaten to death and buried, probably still alive, in a shallow grave. Chater lingered in agony for days. Someone in the gang proposed that they tie a string to a gun, so they could all pull the trigger at once. But the days of wittering and spasmodic, brutal torture ended with Chater dropped to the bottom of a lonesome well and pelted with stones until he finally expired, savagery exceeding even the smugglers’ violent reputation.

Suspicion of foul play was immediate with the discovery of Galley’s bloody coat near the road. The government quickly offered a reward for any information, but the smugglers’ omerta meant that it would be months before everyone’s worst fears were confirmed. An anonymous tipster revealed the location of the bodies, and implicated William Steele, alias Hardware, in the murders. Steele, clearly understanding the trouble he was in, turned King’s evidence.

Steele’s testimony went straight to the very top of the British political world, including the Prime Minister. The south-east coast of Britain had been infested with violent smuggling gangs for decades, but the terrible, protracted violence of the murders had focused the political elite on the problem more than dry accounts of lost revenues ever could. Smuggling wasn’t just a loss on a ledger anymore, it was a man buried alive and a young, bloodied body at the bottom of a well.

But one man would take the horror of Steele’s testimony and turn it to action, the Duke of Richmond, a powerful Sussex landowner and general who had been fighting Jacobite rebels in North England a few years earlier. He knew war and its violent terrors, but there was a new horror right on his doorstep. He would crush the smugglers like the government had crushed the Jacobites.

Richmond was not only going to hunt down the murderers, he would also put whatever Sussex smuggler he could find in a noose. What started with the murders turned into a purge of the whole Sussex smuggling community. Smugglers were arrested, tried and hanged for whatever charge Richmond and his men could prove, be that smuggling, robbery, or murder.

The campaign would not end smuggling in the Southeast, but it ended the Hawkhurst Gang’s reign of terror in Kent and Sussex. Richmond, under the pseudonym ‘The Gentleman of Chichester’ would publish an account of the murders and the subsequent trials. The account, called A Full and Genuine History of the Inhuman Murders of William Galley and Daniel Chater would go through multiple editions and remain in print at least until the 1830s. Galley and Chater were murdered in the heart of Sussex’s gangland during one of the most violent periods of the 18th century. Their deaths would help end a very violent chapter in British history.